Project results in assembly of “traveling trunk” of artifacts, bringing history/culture alive

PORTSMOUTH – Researchers from Great Bay Community College and the University of New Hampshire are examining the working conditions and lifestyles of the people who worked at the Appledore Hotel on the Isle of Shoals during the luxury resort’s heyday in the late 19th century.

PORTSMOUTH – Researchers from Great Bay Community College and the University of New Hampshire are examining the working conditions and lifestyles of the people who worked at the Appledore Hotel on the Isle of Shoals during the luxury resort’s heyday in the late 19th century.

As a result of their research, the scholars are assembling a “traveling trunk” exhibition that will display photos, letters, artifacts, and other items unearthed during their research, or their replicas. The trunk represents a Victorian-era steamer trunk that would have been common among wealthy travelers who arrived at the hotel for their exotic north Atlantic getaway.

“The idea is to have it as a vessel that can quite literary be moved around and travel from place to place, filled with material objects, reprinted writings, letters, pages from diaries, and contextual materials with things like billiard balls, representing some of the recreation of the time, or pieces of lace for a representation of the clothing,” said Jordan A. Fansler, professor of social science and history program coordinator at Great Bay. “When it’s finished, it can be taken around and displayed and become a miniature exhibition for use in classrooms, public libraries or high schools.”

Eleanor Harrison-Buck, professor of anthropology and chair of the Anthropology Department at UNH, said the Traveling Trunk idea was inspired by a program offered by the Tennessee State Museum. “Our aim with the Traveling Trunk is to bring the Seacoast history and culture alive for our students on campus and in the classroom at UNH and Great Bay and potentially other schools across the state,” she said.

Eleanor Harrison-Buck, professor of anthropology and chair of the Anthropology Department at UNH, said the Traveling Trunk idea was inspired by a program offered by the Tennessee State Museum. “Our aim with the Traveling Trunk is to bring the Seacoast history and culture alive for our students on campus and in the classroom at UNH and Great Bay and potentially other schools across the state,” she said.

The hotel on Appledore Island on the Isles of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire and Maine was among the earliest luxury destinations in America, and it attracted international attention for its remote, rugged location, spectacular gardens, and opulent accommodations. The hotel opened in 1848, burned to the ground in 1914 and was never rebuilt. Its most popular period was a relatively brief slice of time from the 1860s to about 1900.

“A lot of the Appledore story is pretty well known. What we were interested in were the inner workings of the hotel,” Fansler said. “The showcase of Appledore doesn’t happen without all the work underneath. That is the story we wanted to tell.”

It is the lives of the wealthy elite that usually take center stage in the history of the Grand Hotel Era on the Seacoast, but the research team aimed to uncover a fuller story. “Because this project is focused not just on the wealthy elite, but the hotel employees, many of whom were immigrants, we are now gaining a more diverse perspective and fuller understanding of the past,” Harrison-Buck said.

When it comes to immigrant history on the Shoals, most are familiar with the infamous Smuttynose Murders of 1873, which involved an axe murderer of Prussian descent and his victims who were Norwegian immigrants. “What most people don’t know is that one of the Norwegian victims, Karen Christiansen, was an employee of the Appledore House,” said UNH anthropology student Kieran Mulligan. “From Karen, we get a window into the lives of the Norwegian immigrants on Appledore,” he added.

The Great Bay-UNH research team, supported by a grant from the New Hampshire Humanities Collaborative, spent the summer going over records, diaries, and other ephemera from the island’s labor force, while also scouring the island for artifacts on the surface. Their initial archaeological survey of the island this summer revealed the foundations of the hotel ruins and associated buildings on the backside of the hotel where the employees lived and worked.

The Great Bay-UNH research team, supported by a grant from the New Hampshire Humanities Collaborative, spent the summer going over records, diaries, and other ephemera from the island’s labor force, while also scouring the island for artifacts on the surface. Their initial archaeological survey of the island this summer revealed the foundations of the hotel ruins and associated buildings on the backside of the hotel where the employees lived and worked.

Much of the building foundations are still intact, and the hotel’s famous gardens have been revived. The island, slightly less than 10 miles from Portsmouth, is home to Shoals Marine Laboratory, jointly operated by UNH and Cornell University.

Great Bay history student Alec Momenee-DuPrie dug into the lives of the immigrant workers at the hotel to contrast them with the lives of the upper-class guests. “I wanted to explore that dichotomy, because classism is something I have always been interested in,” he said.

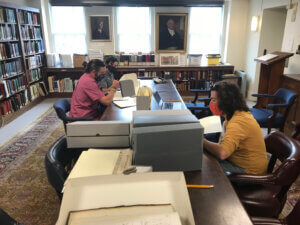

While he spent time on the island itself, he did most of his research at the Portsmouth Athenaeum, where he found newsletters for hotel employees and the diary of a woman who worked at the hotel in 1906. “The diary offers details of the fun and the not-so-fun part of her life,” said Momenee-DuPrie, who is on track to graduate this year and plans to continue his education at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada. He and another undergraduate researcher Kieran Mulligan, now a senior at UNH, worked together to uncover information about the daily experience of the hotel employees.

In contrast to the hotel worker, who wrote in her diary about sneaking out of her sleeping quarters at night and making use of the amenities intended for guests, there were the wealthy travelers who were drawn to the hotel’s high-end food, tennis court and bowling alley – cutting-edge amenities at the time, where fun and games awaited. Fansler said they found on the hotel ruins glass bulbs that were used as insulators for telegraph wires, and in the archives the train schedules from Washington, D.C., as well as advertisements touting the hotel in distant cities. Harrison-Buck also noted finding a hotel “rule book” in the archives dating to around the turn of the century that shed some light on the strict dress code and stringent conduct that was expected of hotel employees.

They found photos of the children of hotel guests lounging by the pool and photos of the hotel workers doing laundry. Fansler described the juxtaposition of the wealthy guests and the laborers who worked behind the scenes as a classic “front-of-house, back-of-house, upstairs-downstairs kind of divide.”

Momenee-DuPrie appreciated the chance to collaborate with other students and researchers on a professional study. “It showed me what that process is like. When doing research outside of school, you must have a purpose and an end goal to communicate to the outside world. Until now, I had only written for my professors or other students,” said Momenee-DuPrie, 22, who lives in Newfields.

Mulligan was also excited to be involved in a research project where he was able to get hands-on experience working in the archives, reading and interpreting original primary source material. “I never had to produce a formal, public-facing project like this one. But most importantly, I felt a sense of justice from working on the project,” he said. “No one is talking about these workers, but they have a story, they have lives beyond washing linens. I got to tell their stories, in my experience that is the greatest reward,” he added.

Mulligan was also excited to be involved in a research project where he was able to get hands-on experience working in the archives, reading and interpreting original primary source material. “I never had to produce a formal, public-facing project like this one. But most importantly, I felt a sense of justice from working on the project,” he said. “No one is talking about these workers, but they have a story, they have lives beyond washing linens. I got to tell their stories, in my experience that is the greatest reward,” he added.

Fansler said the ability of students and faculty at the community college and university levels to collaborate on meaningful research is the strength of the New Hampshire Humanities Collaborative (NHHC), which is funded by a multi-year grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The NHHC has been fostering links between the Community College System and UNH through programs, research projects, and initiatives designed to ease transitions and increase connections between the institutions for over 3 years.

Harrison-Buck pitched the idea of the Shoals-Seacoast Archaeology project to the NHHC and they brought Fansler and Harrison-Buck together at their (virtual) Winter Academy last January. Harrison-Buck stated, “their aim was to bring together faculty from the College of Liberal Arts at UNH and the state’s community colleges who might form productive collaborations. And it worked!” Bringing together their knowledge of historical archaeology and the archives in Portsmouth is what made the project such a success. Harrison-Buck noted that Fansler’s knowledge of 19th century history and his prior experience researching the archives at the Portsmouth Athenaeum were particularly helpful, and the faculty-student collaboration was “incredibly rewarding,” she said.

It reflects well on Great Bay when humanities students participate in university-level research, Fansler said, adding that he is currently working on another political science research project to pursue through the Humanities Collaborative.

Great Bay has about 20 history majors and UNH has roughly 60 majors in anthropology, of which archaeology is a sub-discipline. In an era of disinformation and at a time when people are looking to the past for lessons, Fansler and Harrison-Buck both agreed that student interest in these programs has been growing. History and archaeology teach students to think critically, analyze sources of data, including archives and artifacts to determine the trustworthiness of historical information, and then process that evidence to reconstruct what life was really like for people in the past—not just for the elite but in their case for the working class as well.

“What’s great with a project like this is that it is deeply rooted in local history. When it is local like the Isles of Shoals, it opens up the idea of what has been there before and what our connections are to the past. Frankly, there is no present without the past,” Fansler said. Whenever he hears someone ask why something is the way it is, he directs them to the past.

Harrison-Buck notes the explicit connections between past and present conditions of immigrant status and privilege. “Our work is not just about telling the past; it is showing the legacy of ‘high’ culture and politics that continues to shape inequities for the ‘other’ in New Hampshire and across America today.” “The answer is there in the history,” Fansler adds. “There are trends that create these through lines that we can look at, study, and understand. History does not predict the future, but it helps us understand what is happening in the present. Everything has a history. There is a story behind every trend, every person, every place.”

Great Bay Community College is a comprehensive postsecondary institution offering quality academic and professional and technical education in support of workforce development and lifelong learning. Great Bay Community College is part of the Community College System of New Hampshire, a public system of higher education consisting of seven colleges in Berlin, Claremont, Laconia, Concord, Manchester, Nashua, and Portsmouth. The colleges offer Associate degrees and career training in technical, professional and general fields, including transfer pathways to baccalaureate degrees. For more information on Great Bay Community College, visit www.greatbay.edu.